On fireplaces

Fireplaces. They were one of the key components of the Victorian-era home in Christchurch, in the sense that, like doors and windows, every house had one (I’m somewhat taking liberties with the definition of fireplace here, and counting a coal range as one). Fire, after all, was required for cooking (at least until the advent of gas, if you want to distinguish that – if you do, gas cooking stoves were being advertised in Christchurch papers from the late 1870s (Press 23/11/1878: 8)). The other essential service that fireplaces provided, of course, was heating, although you have to wonder just how much heat these often quite small fireplaces generated, particularly given the high stud and large size of some of these Victorian rooms, not to mention the lack of insulation. No wonder the Victorians wore so many clothes…

This coal register bears the words “THE CONGO”, with the bust of a mustachioed figure above. The bust is possibly that of Henry Morgan Stanley, who searched for the source of that river. Stanley was also known for his brutality towards African people.

Most houses from the sample I analysed for my PhD research did have more than one fireplace, and those that had only one were amongst the smallest of the houses – and thus amongst the most cheaply built, and occupied by poorer families. For context, in 1883, a double chimney with a cement hearth cost £10-£11 (and the mantelpiece was more in addition to this). Such a cost would have been more than 10% of the cost of building the cheapest cottage described in Brett’s Colonists’ Guide (Leys 1883: 725). Most houses had between two and five fireplaces and, unsurprisingly, the number of fireplaces increased with the number of rooms. But not always: one 11-room house had just two fireplaces and a 14-room house had three. Which, as I write this on a frosty Canterbury morning, seems like it would have particularly cold. But does provide an insight into how people chose to spend their money when building a house, with these families seemingly favouring space over heating (which seems less than ideal, given that increasing the size of a house would have increased the heating requirements).

For those who are interested in such statistics: on average, houses built by working class families had three fireplaces, while those built by middle and upper class families had four fireplaces. Which, if nothing else, serves to prove how minimal the differences between these occupational classes and the houses they built were (although the statistics tell me that these differences were “significant”).

A rather elaborately carved mantelpiece, found in a surprisingly plain house in St Abans.

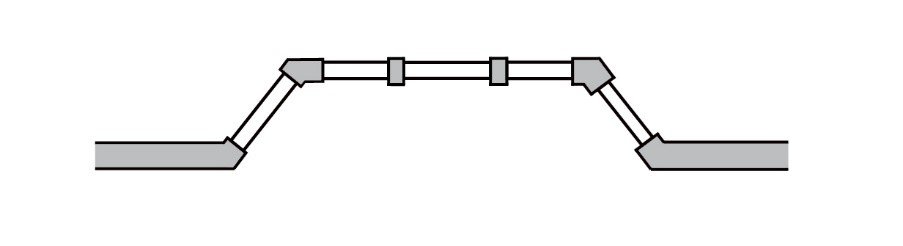

If a house had just the one fireplace it was, of course, in the kitchen. If there were two fireplaces, the second was almost always in the parlour (or at least, the room intended to have been used as the parlour – some may have functioned as master bedrooms, depending on the size of the family). When there were two fireplaces, they were usually back-to-back, meaning that they shared the same chimney – this would have been cheaper to build than two standalone fireplaces. When there was a third fireplace, it was usually in the master bedroom. A fourth fireplace could go anywhere. Well, not quite. That somewhat flippant remark reflects the fact the houses with four fireplaces had greater complexity, both in the number of rooms and the range of room functions, meaning that there were more options in terms of where to put a fireplace. In general, though, if a room was designed to entertain people, it had a fireplace and, if it was a service room, such as a pantry, scullery or bathroom, it did not. Likewise, an analysis of plans for grand homes in 19th century Christchurch indicates that servant’s bedrooms were highly unlikely to have a fireplace. Which seems a little mean, but in fact few of even these houses had fireplaces in all the family bedrooms. Fireplaces were also unusual in halls, except in the very grandest of homes – Riccarton House, I’m looking at you.

Fireplaces, of course, required fuel, which could be either wood or coal. In the early days of Christchurch’s European settlement, wood is more likely to have been used than coal, as coal had to be imported and would thus have been relatively expensive. Wood, though, was not without its own problems. In late 1861, there was something of a firewood crisis: prices rose dramatically as men who had formerly worked in logging were lured away by the gold rushes (Lyttelton Times 15/8/1860: 4, 29/1/1862: 4). This led to the formation of the Christchurch Coal and Firewood Society (those Victorians did seem to feel like any problem could be solved by a society…; Lyttelton Times 25/9/1861: 6). The aim of the society was to use its larger purchasing power to obtain coal and firewood at a reasonable price for its members – as a bonus, it would also ensure the quality of the wood, that the correct amount was delivered and that it was stacked for you (Lyttelton Times 29/1/1862: 4, 5/2/1862: 5; Press 5/10/1861: 3). In theory, at least – letters to the editor indicate that this was not always the case (Lyttelton Times 5/2/1862: 5). The society also struggled to obtain sufficient wood (Lyttelton Times 29/1/1862: 4). Such factors no doubt contributed to its demise some six months after it was formed.

Some rather glorious fireplace tiles, featuring an intriguing combination of romantic imagery and strawberries. A reference to Strawberry Hill? Who knows. Image: K. Webb, Ōtautahi Christchurch archaeological archive.

What fireplaces did not require were fancy mantelpieces and fire surrounds, but being Victorians, many simply could not resist this possibility (fireplaces also didn’t require fancy chimneys but, seeing as all this analysis relates to post-earthquake recording, there was not a single surviving chimney top amongst the houses in my sample). Unsurprisingly, parlour or drawing room fireplaces were typically the most ornate in the house, and fireplaces became less decorative as the importance of the room declined. This blog from our friends at Underground Overground Archaeology has a few more examples of fabulous fireplaces.

Fireplaces fulfilled some basic needs in houses in 19th century Christchurch: they kept people warm and they provided a means of cooking. To be fair, the warmth factor is debateable – perhaps it’s more accurate to say that they provided an illusion of warmth… And good cheer, for who amongst us does not enjoy the warming crackle of a (safely contained) open fire? Fireplaces, too, could provide an indication of a room’s importance and particularly whether or not the room in question was intended to entertain guests. As with so many architectural features, then, fireplaces fulfilled a practical purpose and a decorative one, and there were messages of wealth and status continued within that decorative aspect.

Katharine Watson

References

Leys, T. W., 1883. Brett’s Colonists’ Guide and Cyclopedia of Useful Knowledge: Being a Compendium of Information by Practical Colonists. H. Brett, Auckland.

Lyttelton Times. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Press. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers