Allow me to introduce you to Henrietta Madoline Yaldwyn (née Yeend). It’s 1883 and Henrietta and her husband, William, and their four children have just moved to Christchurch (BDM Online n.d., Star (Christchurch) 3/5/1883: 3). This was but the latest in a succession of moves for Henrietta. She was born in Melbourne (to English parents) and grew up between that city and Hobart (McCallum 2025). By 1863, the Yeend family, including Henrietta, was living in Dunedin, and it was here that she met William Butler Yaldwyn (Otago Daily Times 3/9/1863: 7). Henrietta and William married in 1868 (McCallum 2025). A few years later they spent some time in England (where William was born), before returning to New Zealand, living first in Dunedin and then in the lower North Island (Evening Star 24/2/1875: 3, Otago Daily Times 25/3/1871: 1, Star (Christchurch) 3/5/1883: 3). Regrettably, William, an accountant, went bankrupt in 1878 – a not uncommon occurrence for 19th century colonial settlers (Evening Post 7/3/1878: 3).

After William had a stint in government employment in the lower North Island, the family found their way to Christchurch (Star (Christchurch) 3/5/1883: 3). By 1884, Henrietta and William had taken up residence in a rather impressive-looking newly built house on a quarter-acre section in Hereford Street east (Lyttelton Times 3/5/1884: 7). They rented this property from George Fletcher, a tailor (LINZ 1878). By now, the eldest of the children was 15, with the youngest – and only daughter – being three years old (BDM Online n.d.). William set himself up as an accountant in their new city. And Henrietta? Well, she establishes a school for “young ladies”, to be known as ‘Aorangi’ (Lyttelton Times 3/5/1884: 7). Why Aorangi? To be honest, your guess is as good as mine. Actually, not quite. I was intrigued by this and so did some research on colonial setters’ use of Māori words for house names. You can read all about it here.

The first advertisements for Aorangi, Henrietta’s school. Note the reference to being assisted by “competent teachers”. Image: Lyttelton Times 3/5/1884: 7.

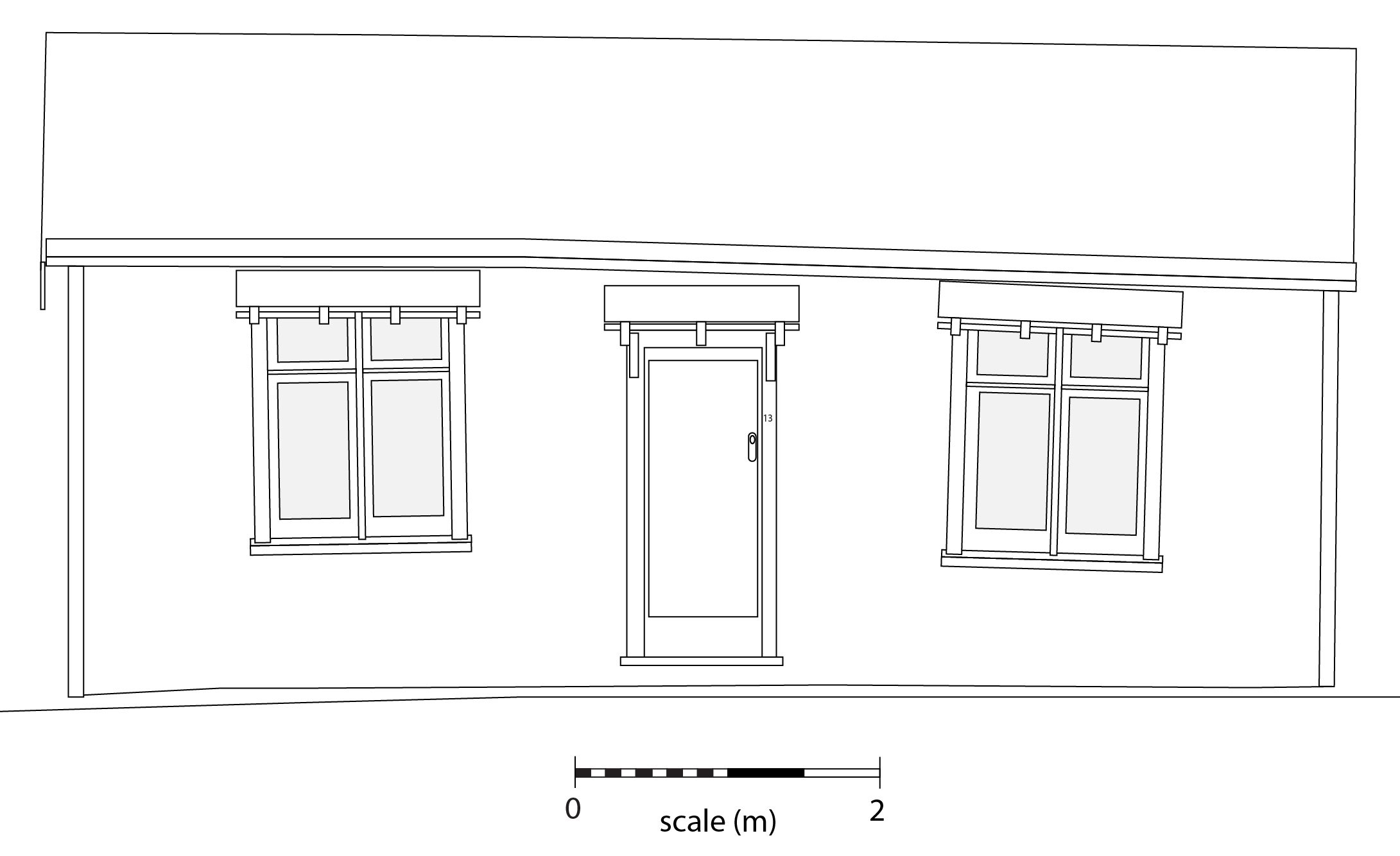

Let me tell you a little bit about the house, because it was a little bit unusual. You see, any passerby on Hereford Street would have thought it was two-storeyed. And part of it was. Crucially, though, not all of it. In fact, the two-storeyed part was only one room deep, whereas the house itself was three rooms deep. So, like any number of 19th century villas, this house was built to look bigger than it was – to create an impression of wealth and status that didn’t actually exist. More than that, two-storeyed houses were by their very nature – their scale, their bulk – more imposing than their single-storeyed equivalents. Living in a two-storeyed house, particularly a large fully detached one, was a sign of wealth and status. The house was clad in rusticated weatherboards and had wooden quoins on the corners. Quoins were often used to give the impression that a building was stone, as opposed to wooden, but in the case of many domestic buildings, it would have been perfectly obvious that the house was wooden and no deceiving even the most casual of observers. As such, I think of these as little more than decorative. The other unusual feature of the house was the French doors on the ground floor, which opened from the veranda into the two front rooms. French doors were not a common feature of houses in 19th century Christchurch, being more typically associated with an earlier era of architecture.

Aorangi, in 2013. Image: L. Tremlett, Ōtautahi Christchurch archaeological archive.

The house had 11 rooms (including two halls). Based on my understanding of life in 19th century houses in Christchurch, and Henrietta and William’s occupational status, I think that one of the front rooms would have been the parlour (or drawing room), and the other was probably used as the school room, thus minimising the movement of students through the house. The other rooms on the ground floor would have been a dining room, kitchen and scullery. On the first floor were three bedrooms and what was probably a linen closet.

The east elevation of Aorangi, showing the two-storey and one-storey components. Image: L. Tremlett and K. Watson, Ōtautahi Christchurch archaeological archive.

It was by no means unusual for women to run schools in 19th century New Zealand. In fact, it was one of the more widely ‘accepted’ professions for women, particularly if that school was for young women (Bishop 2019: 71, 75). The theory went that teaching drew on all those ‘nurturing’ attributes women were supposed to have, and was really just an extension of their roles as mothers. More importantly, it was a relatively accessible profession. No training was required and, if the school was in the house one was already living in, little money was required to establish the school (Pollock 2012). I’ve not been able to find any evidence that Henrietta had run a school – or worked as a governess or teacher – prior to establishing Aorangi, but that’s not to say that she didn’t.

Little information is available about Aorangi the school. The advertisement about ‘young ladies’ indicates it catered to girls in their teens, as opposed to younger girls. As to the subjects taught, they are likely to have been what Catherine Bishop describes as “the requisite feminine accomplishments”, such as drawing, painting, music, dancing, sewing and/or embroidery (Bishop 2019: 75, 88). French may also have been an option, but science is unlikely to have been taught, although there may have been some basic mathematics (Bishop 2019: 87).

Henrietta only ran the school until c.1885/86, when the family appear to have continued their somewhat peripatetic existence (I think they went to Australia at this point). But her school continued without her. It was taken over by “The Misses Buchanan” (Lyttelton Times 23/1/1886: 7). The Misses Buchanan, who ran the school as a boarding school for a time, are frustratingly elusive. Jessie Henrietta Buchanan arrived in New Zealand in c.1851 and was involved with the school for longer than the other ‘Misses’, one of whom disappears from view in the early 1900s (Elizabeth Marion) and the other marries at around the same time (Gertrude E.). As best I can tell, Elizabeth Marion and Gertrude were Jessie’s nieces. Elizabeth, their mother, also lived at the house. Elizabeth was a widow when she arrived in New Zealand in c.1878 and is described as a ‘lady’ in the electoral rolls, neatly distinguishing her from her working female relatives, who also presumably supported her financially. So, too, William L. Buchanan, possibly Elizabeth’s son. Jessie ran the school until at least 1916, by which time it focused solely on dancing (Press 29/6/1916: 11). Of note is that it’s always Jessie who’s listed as the main resident of the house in the street directories, never William, which is highly unusual – if there was a man in the house, he was typically the resident listed.

The first advertisement the Misses Buchanan placed for Aorangi. Image: Lyttelton Times 23/1/1886: 7.

At face value, this is just a story of a house and the women who lived there in the 19th century. But it encapsulates so much more than that: how women could earn a living in 19th century Christchurch; how houses could deceive – or, at least, be used to enhance one’s story; how houses could be used to generate an income; the peripatetic lives of some colonial settlers (side note, my research to date indicates that this was not the norm – people mostly came and stayed); the role and importance of class, social status and gender; and the ways in which family ties could shape immigration, opportunities and life choices. Which, to my mind, just goes to prove the importance of ‘stories’, and of their power to help us understand the past.

Katharine Watson

References

BDM Online, n.d. Available at: https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz/home

Bishop, Catherine, 2019. Women Mean Business: Colonial Businesswomen in New Zealand. Otago University Press, Dunedin.

Evening Post (Christchurch). Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Evening Star (Christchurch). Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

LINZ, 1878. Certificate of title 33/144, Canterbury. Landonline.

Lyttelton Times. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

McCallum, D., 2025. Henrietta Madoline Yeend. Ancestry. [online] Available at: https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/37131698/person/360146005877/facts

Otago Daily Times. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Pollock, Kerryn, 2012. Tertiary education – colleges of education before 1990. Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. [online] Available at: https://teara.govt.nz/en/tertiary-education/page-3 [Accessed 30 January 2025].

Press. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Star (Christchurch). Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers