When I started doing my doctoral research, one of the things I wanted to know was whether or not the houses women built were different from those men built. A naïve question, it turned out. The fundamental flaw was, in the absence of detailed archival records, how do you know if a woman built the house? (And by ‘built’ I mean, commissioned the construction of the house and had significant input into the design, form, layout and appearance of the house.) I analysed 101 houses from 19th century Christchurch for my thesis, and just two of them were built by single people. The remainder were built by people who were married and my assumption throughout was that such houses were built by the couple, rather than by just one of them. It’s often assumed that the person who owned the land (and took out the mortgage) built the house, as opposed to seeing this as a joint project by a married couple. This is an approach shaped by the landownership factor and also by the reality that men tended to be the financial provider in the 19th century Anglo world. There’s an assumption that extends from here to chief decision maker, although there’s no real justification for this.

Plenty has been written about women and houses in the 19th century, most of it in the context of Victorian society in England or the United States. It tends to revolve around the ideal promoted by advice books of the day that the house should be a private, domestic space, created and curated by women to provide men with respite from the evils of the (public, working) world, and in which to raise good moral, Christian children. It’s an ideal that’s often used to suggest that certain spaces within a house were feminine – the drawing room – and others masculine – the dining room – and also that men were responsible for the construction of the house, and women for its interior decoration (it’s easy to see where more recent stereotypes about the gender of architects and interior decorators have their origins). For various reasons (which I don’t have the time, space or inclination to go into today), it’s not an ideal that I think is particularly relevant to the analysis of houses in colonial settler New Zealand (with thanks to my thesis supervisors for helping me get to this point!).

This house was built on land owned by Rose Anna King . Regrettably, I’ve not been a to find out a thing about Rose (I don’t even know if that turret was original), except that she had no children. Image: Ōtautahi Christchurch archaeological archive.

What, then, can houses tell us about the lives of women in colonial settler society in New Zealand? Quite a lot, I think, but today I want to focus on just one response to that question: they make women more visible, particularly when the construction of the house is framed within the context of a series of decisions made by a couple, as opposed to just the landowner. This point notwithstanding, for the sake of argument (and brevity), today I’m going to focus on some of the 11 houses from my thesis that were built on land owned by women, because this is a situation that particularly foregrounds women. In making these individual women visible, we can learn about women’s experiences more broadly.

These houses highlight that, while it was not common for women to buy or own property in 19th century Christchurch, it wasn’t unusual either. Where the women came by the money to fund these purchases is not clear, and it’s not clear if it was their own money or their husband’s money that was used (women sometimes came into marriages with endowments from their families, although this was typically the preserve of the wealthy). Only one of the women came from an obviously wealthy backgrounds (more on this below) and it’s possible that, in some instances at least, the property was in the woman’s name because of her husband’s financial troubles.

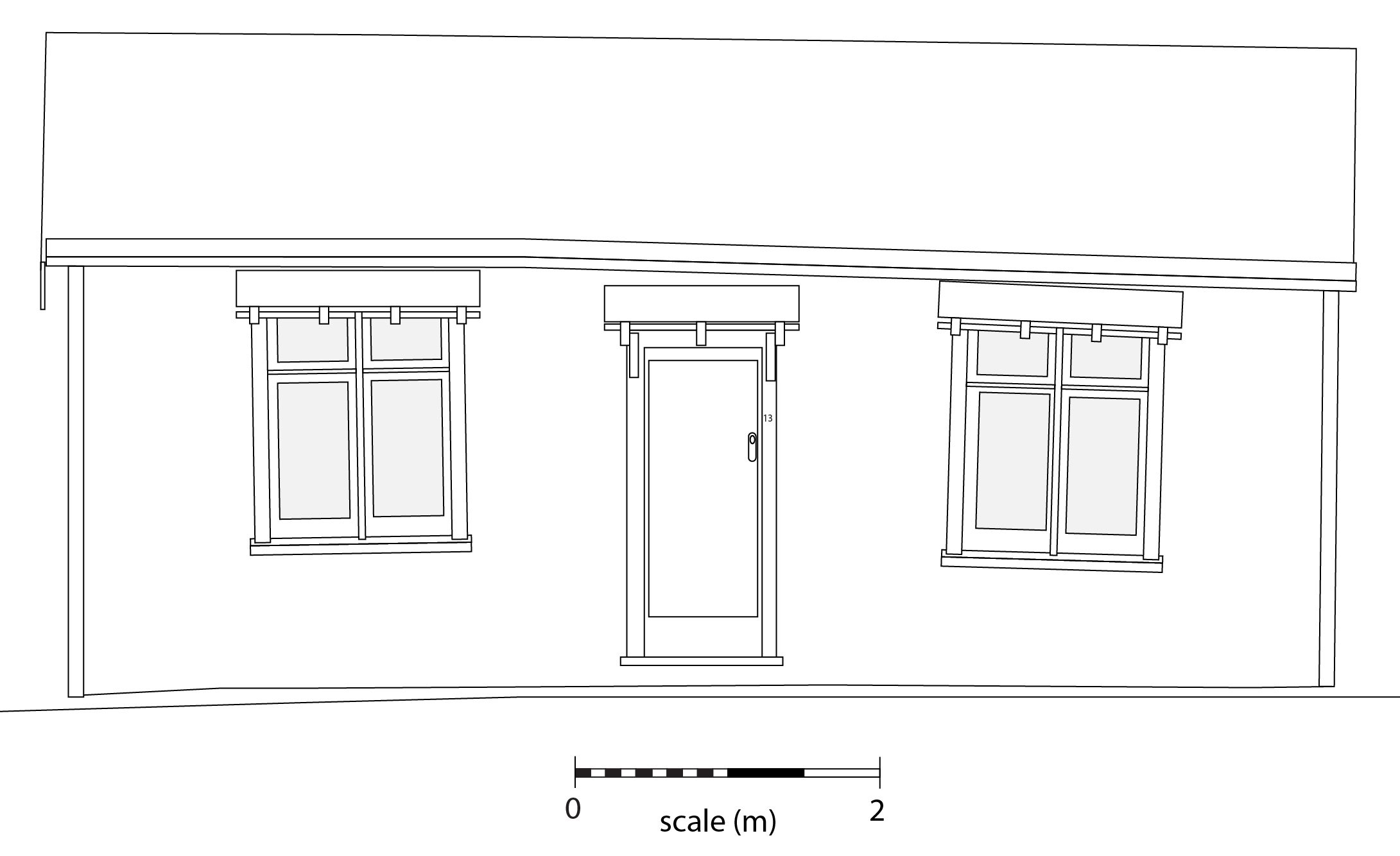

Margaret Stinnear (possibly née Stewart) purchased this land parcel and the adjoining one in 1893 and built two identical rental houses on them (LINZ 1893). Two years previously, her husband’s business had been the subject of a mortgagee sale and, on these grounds, it’s tempting to suggest that his financial woes led to this situation (Lyttelton Times 13/6/1891: 8). However, Margaret would go on to own a number of properties and I suspect it was her financial acumen that kept the family afloat, even financing two return trips to England (Lyttelton Times 3/10/1903: 9, Press 6/10/1908: 12, 24/2/1912: 14). Her estate was worth £2500 at her death in 1911. Another intriguing detail of Margaret’s life is that her only child, a daughter, was adopted (Stinnear 1911). Image: C. Staniforth, Ōtautahi Christchurch archaeological archive.

These women were all either working or middle class. Three were the daughters of farmers. Others were daughters of a carter, a miner, a stone mason and a stone quarrier, all working class occupations. Two of the women are known to have worked before they came to New Zealand. The fabulously named Matilda Sneesby (née Baker) was a stillroom maid in Marylebone, London, while Fanny Jane Langford (née Waite) worked as a nail maker even after her marriage (KenLederer 2025, Walandheather 2025). As noted above, none of the women are likely to have had money from their family – with one exception (see the picture below). Another would go on to be quite socially prominent, counting premiers and the like amongst her circle (Timaru Herald 19/12/1908: 2). But, for the majority of these women, their class background, and the fact that they were able to buy property in Christchurch, is a testament to the much greater opportunities available to working (and even middle) class families in New Zealand than in the British Isles.

Prudence McClurg (née Bassett) almost certainly used family money to buy the land this house was built on. She certainly bought it from one uncle and subsequently mortgaged it to another (LINZ 1894, 1897). She was part of a complex family network of Irish immigrants, a number of whom were quite commercially successful and, between them, owned quite a bit of property. Image: P. Mitchell, Ōtautahi Christchurch archaeological archive.

And what of the houses these women built? Well, they were mostly quite modest, with just one bay villa amongst them. The rest were mostly standard villas, with two being standard cottages, indicating a low level of capital. Similarly, most of them had a villa layout, although again there were two with a cottage layout. In fact, most were typical Christchurch houses – which may go some way towards answering my original question? And, perhaps also testify to the predominance of the plain, flat-fronted, symmetrical standard villa in Christchurch, and everything that was embodied in that. The houses ranged in size from five to 10 rooms, and the women had varying numbers of children. Two of the women had no children, a situation my research indicates would have been unusual, and this on its own makes these women stand out (perhaps it is more than coincidence that these are the two women about whom I have the least information, but perhaps not). Maria Hardie, on the other hand, had seven children (two of whom did not survive infancy). Her family would have lived in particularly cramped conditions in their tiny cottage. Under these circumstances, it’s highly unlikely Maria’s family enjoyed the use of a parlour. Most of the families would have lived in more spacious circumstances, with some children no doubt sharing rooms, but still with a parlour, giving them a reasonable amount of living space. Which brings me to one other thing these women had in common: none of them advertised for servants. Of course, this doesn’t mean they didn’t have servants, and the size of the houses the Bassetts and Sneesbys lived in indicates that the servants would have been a possibility for them.

Scroll through the slideshow below to learn more about the women, their houses and their lives. For each of the women, I tried to find at least one factoid that was unrelated to their parents, husband or children, but for a handful this proved just impossible, highlighting how small a trace they left in the historical record.

While these women left little trace in the historical record, in building, they left a physical mark on the city, contributing to its appearance and the development of Christchurch’s own particular style of domestic architecture. In this, we can also recognise that they shared a desire to improve their situation – and those of their families – and the means to act on that desire. While improvement is a motivator for many migrants, not all in the 19th century were fortunate enough to be able to afford to build. I’ve discussed renting in 19th century Christchurch previously, and last week’s post touched on boarding, and there were certainly homeless people in the city These were much more financially precarious positions than these women enjoyed (with the exception of Maria Hardie – follow this link to the blog I wrote about her family to learn more about that). These women, then, draw attention to some of the experiences of women who came to Christchurch in the 19th century. Their lives are by no means representative of a broad cross-section of women, but they show how the stereotypes of women’s lives in the 19th century can be challenged by looking more closely at their individual lives and the houses they built.

Katharine Watson

References

KenLederer, 2025. Fanny Jane Waite. [online] Available at: https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/111401256/person/280097991423/facts

LINZ, 1893. Certificate of title 156/52, Canterbury. Landonline.

LINZ, 1894. Certificate of title 160/219, Canterbury. Landonline.

LINZ, 1897. Certificate of title 173/22, Canterbury. Landonline.

Lyttelton Times. [online] Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Star (Christchurch). [online] Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Stinnear, Margaret Stewart, 1911. Probate. [online] Available at: https://www.familysearch.org/en/search/collection/1865481

Timaru Herald. [online] Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Walandheather, 2025. Matilda Baker. Available at: https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/20142703/person/252127956595/facts